Unfortunately, billions of people around the world have a skewed perception of the true size of countries thanks to a cartographic technique called the Mercator projection. Used just about everywhere, from classroom wall maps to navigation apps, the Mercator projection is the way most of humanity recognizes the position and size of Earth’s continents.

The Mercator Projection

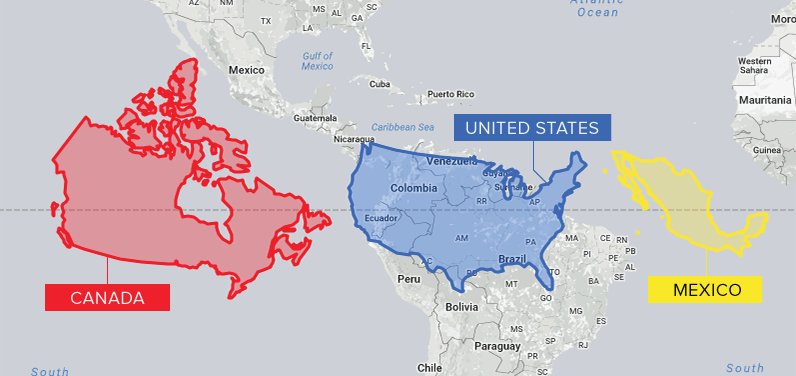

In 1569, the great cartographer, Gerardus Mercator, created a revolutionary new map based on a cylindrical projection. The new map was well-suited to nautical navigation since every line on the sphere is a constant course, or loxodrome. In modern times, this is particularly useful since the Earth can be depicted in a seamless way in online mapping applications. That said, in this projection style, the sizes of landmasses become increasingly distorted the further away from the equator they get. One trade-off for the utility of Mercator’s map is that it pumps up the sizes of Europe and North America. Visually speaking, Canada and Russia appear to take up approximately 25% of the Earth’s landmass, when in reality they occupy a mere 5%. When Antarctica is excluded (as it often is), Canada and Russia’s visual share of landmass jumps to about 40%. Canada is the second largest country in the world, but not by much. Here is an “at scale” look at Canada, the United States, and Mexico.

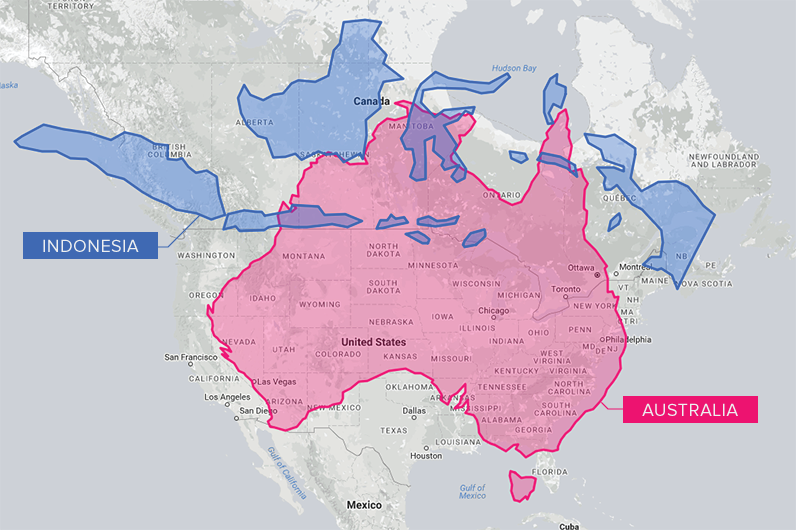

Africa, South Asia, and South America all appear much smaller in relation to countries further from the equator. And from a North American perspective, countries such as Australia and Indonesia appear much smaller than they actually are. Comparing the landmasses on the same latitude as Canada helps put sizes into perspective.

Greenland is the world’s largest island, but looking at its hyper-exaggerated depiction in the map below, you’d be forgiven for wondering why it isn’t a stand-alone continent. In reality, Greenland is about fourteen times smaller than Africa.

Is Bigger Better?

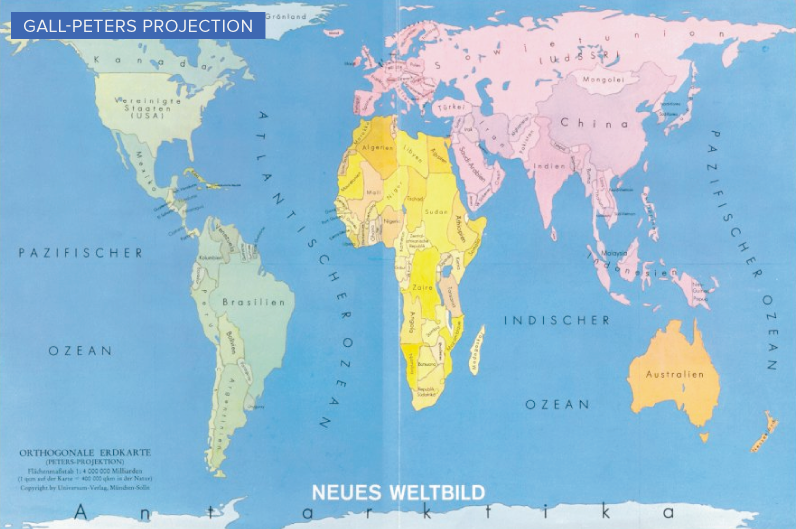

Though Mercator’s map was never intended for use as the default wall map in schools around the world, it has shaped the worldviews of billions of people. Critics of the map—and similar projections—suggest that distortion reinforces a sense of colonialist superiority. As well, the amount of territory a country occupies is often correlated with power and access to natural resources, and map distortions can have the effect of inadvertently diminishing nations closer to the equator. A prime example of this argument is the “True Size of Africa” graphic, which demonstrated to millions of people just how big the continent is. Growing awareness of map distortion is translating into concrete change. Boston public schools, for example, recently switched to the Gall-Peters projection, which more accurately depicts the true size of landmasses.

As well, Google, whose map app is used by approximately one billion people per month, took the bold step of using different projections for different purposes in 2018. The Earth is depicted as a globe at further zoom levels, sidestepping map projection issues completely and displaying the world as it actually is: round.

The Road to Equal-Area Mapping

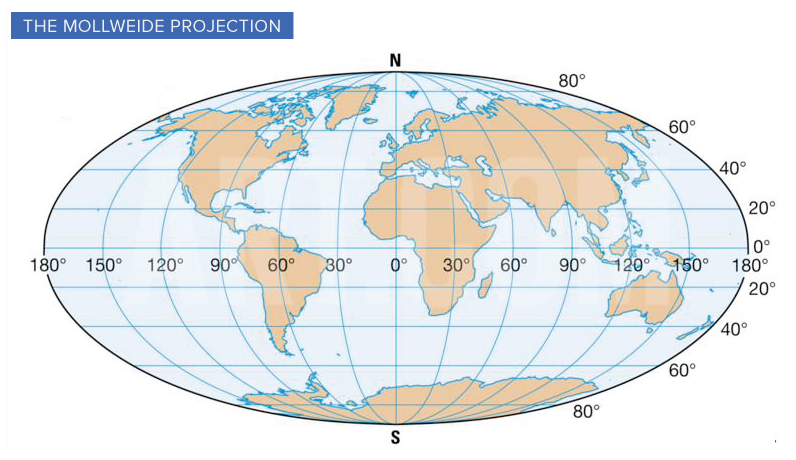

In 1805, mathematician and astronomer, Karl Mollweide, created a namesake projection that trades accuracy of angles and shape for accuracy of proportion. The Mollweide projection has inspired many other attempts at a user-friendly equal area map.

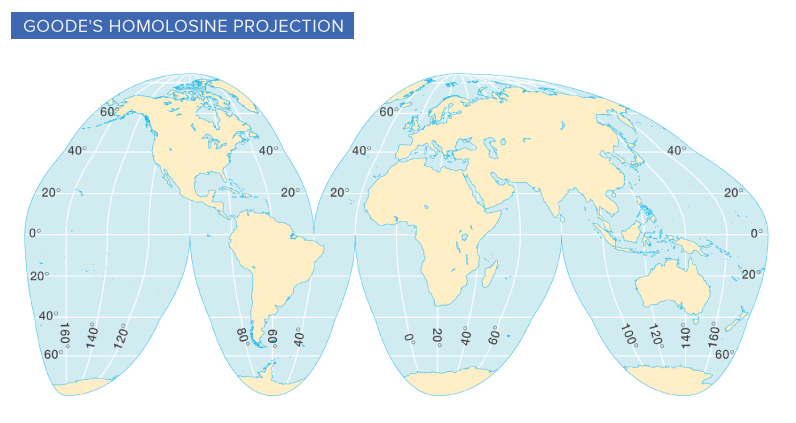

John Paul Goode’s attempt, known as the Goode Homolosine Projection, took this concept a step further by adding interruptions at strategic locations to help reduce the distortion of continents. The resulting shape is sometimes referred to as an “orange peel map”.

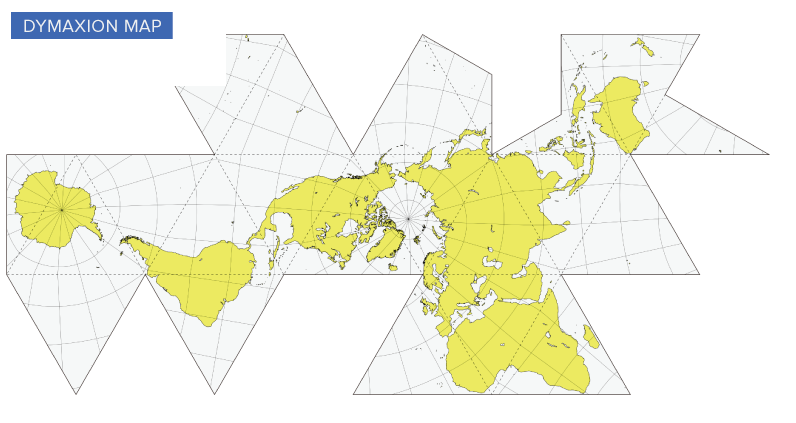

Another evolution in cartography was the Dymaxion map, invented by Buckminster Fuller and patented in 1946. In this version, the continents are no longer in their familiar positions—however, there is more spacial fidelity than in previous projection methods. We’re able to see the true proportions of Africa, Northern Canada, Antarctica, and other distortion hot spots. The Dymaxion map wasn’t created for purely practical purposes. Fuller believed that humans would be better equipped to address global challenges if they were given a way to visualize the Earth’s continents in a contiguous manner.

The AuthaGraph Map

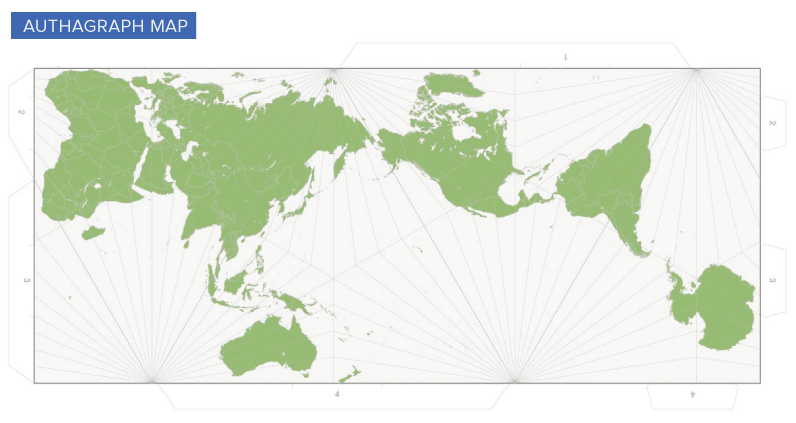

Using a new map-making method called AuthaGraph, Japanese architect, Hajime Narukawa, may have created the most accurate map of the world yet. AuthaGraph divides the globe into 96 triangles, transfers them to a tetrahedron and unfolds into a rectangle. The end result? Landmasses and seas are more accurately proportioned than in traditional projections.

The biggest downfall of the AuthaGraph map is that longitude and latitude lines are no longer a tidy grid. As well, continents on the map are repositioned in a way that will be unfamiliar to a population that is already geographically challenged. That said, depicting our round world on a flat surface will always come with some trade-offs. As demand grows for a true equal-area map, it will be exciting to see what the next generation of map projections have to offer.

Map It Yourself

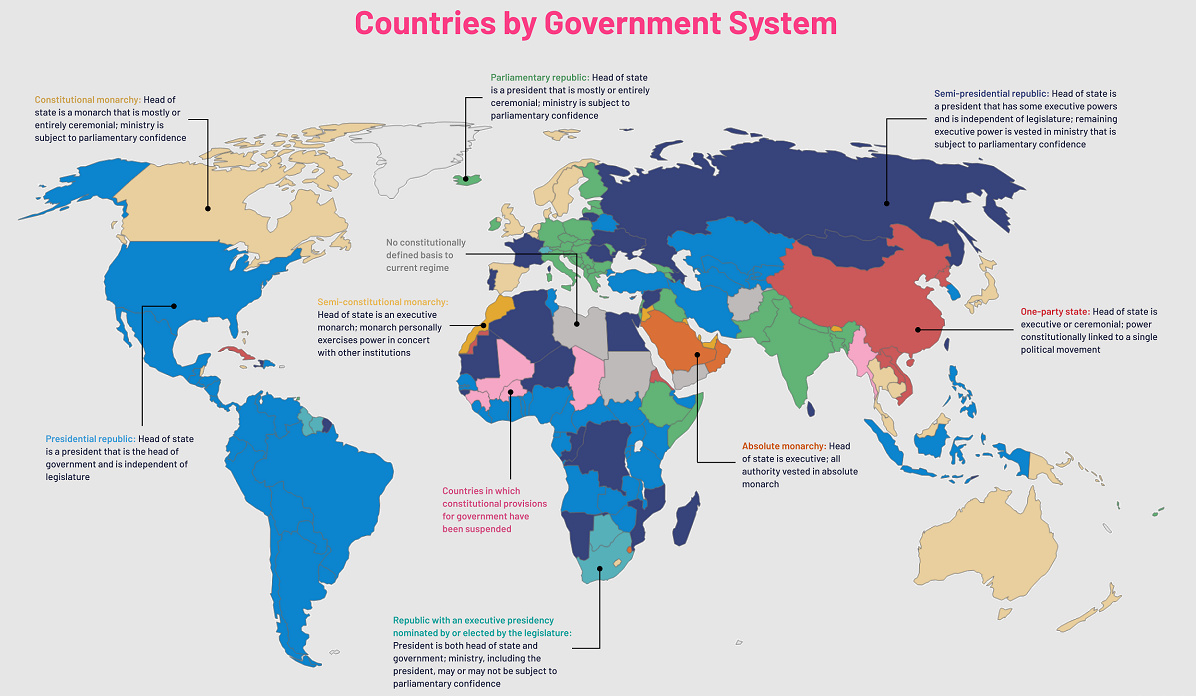

Looking to learn more about maps and map projections? This fantastic tool, created by Florian Ledermann, allows users to take a vast selection of projection styles, and modify them in different ways. This hands-on approach is a fun way to learn how the shape of landmasses shift as the projection changes. on Even while political regimes across these countries have changed over time, they’ve largely followed a few different types of governance. Today, every country can ultimately be classified into just nine broad forms of government systems. This map by Truman Du uses information from Wikipedia to map the government systems that rule the world today.

Countries By Type of Government

It’s important to note that this map charts government systems according to each country’s legal framework. Many countries have constitutions stating their de jure or legally recognized system of government, but their de facto or realized form of governance may be quite different. Here is a list of the stated government system of UN member states and observers as of January 2023: Let’s take a closer look at some of these systems.

Monarchies

Brought back into the spotlight after the death of Queen Elizabeth II of England in September 2022, this form of government has a single ruler. They carry titles from king and queen to sultan or emperor, and their government systems can be further divided into three modern types: constitutional, semi-constitutional, and absolute. A constitutional monarchy sees the monarch act as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, giving them little to no real power. For example, King Charles III is the head of 15 Commonwealth nations including Canada and Australia. However, each has their own head of government. On the other hand, a semi-constitutional monarchy lets the monarch or ruling royal family retain substantial political powers, as is the case in Jordan and Morocco. However, their monarchs still rule the country according to a democratic constitution and in concert with other institutions. Finally, an absolute monarchy is most like the monarchies of old, where the ruler has full power over governance, with modern examples including Saudi Arabia and Vatican City.

Republics

Unlike monarchies, the people hold the power in a republic government system, directly electing representatives to form government. Again, there are multiple types of modern republic governments: presidential, semi-presidential, and parliamentary. The presidential republic could be considered a direct progression from monarchies. This system has a strong and independent chief executive with extensive powers when it comes to domestic affairs and foreign policy. An example of this is the United States, where the President is both the head of state and the head of government. In a semi-presidential republic, the president is the head of state and has some executive powers that are independent of the legislature. However, the prime minister (or chancellor or equivalent title) is the head of government, responsible to the legislature along with the cabinet. Russia is a classic example of this type of government. The last type of republic system is parliamentary. In this system, the president is a figurehead, while the head of government holds real power and is validated by and accountable to the parliament. This type of system can be seen in Germany, Italy, and India and is akin to constitutional monarchies. It’s also important to point out that some parliamentary republic systems operate slightly differently. For example in South Africa, the president is both the head of state and government, but is elected directly by the legislature. This leaves them (and their ministries) potentially subject to parliamentary confidence.

One-Party State

Many of the systems above involve multiple political parties vying to rule and govern their respective countries. In a one-party state, also called a single-party state or single-party system, only one political party has the right to form government. All other political parties are either outlawed or only allowed limited participation in elections. In this system, a country’s head of state and head of government can be executive or ceremonial but political power is constitutionally linked to a single political movement. China is the most well-known example of this government system, with the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China ruling as the de facto leader since 1989.

Provisional

The final form of government is a provisional government formed as an interim or transitional government. In this system, an emergency governmental body is created to manage political transitions after the collapse of a government, or when a new state is formed. Often these evolve into fully constitutionalized systems, but sometimes they hold power for longer than expected. Some examples of countries that are considered provisional include Libya, Burkina Faso, and Chad.