A statement that is as profound as it is banal. In other words, when we do history, we’re a bit like tourists. If we really want to understand the past, we have to think like a local. The infographic above, Aspects of Principal Exports of Chinese Goods to Foreign Countries, is the first in a series that we’re calling Vintage Viz, which presents a historical visualization along with the background and analytical tools to make sense of it. Today, the People’s Republic of China is the second largest economy in the world, a permanent member of the UN Security Council, and a growing military power. But at the dawn of the 20th century, things were much, much different.

Opium and the Opening of China to the West

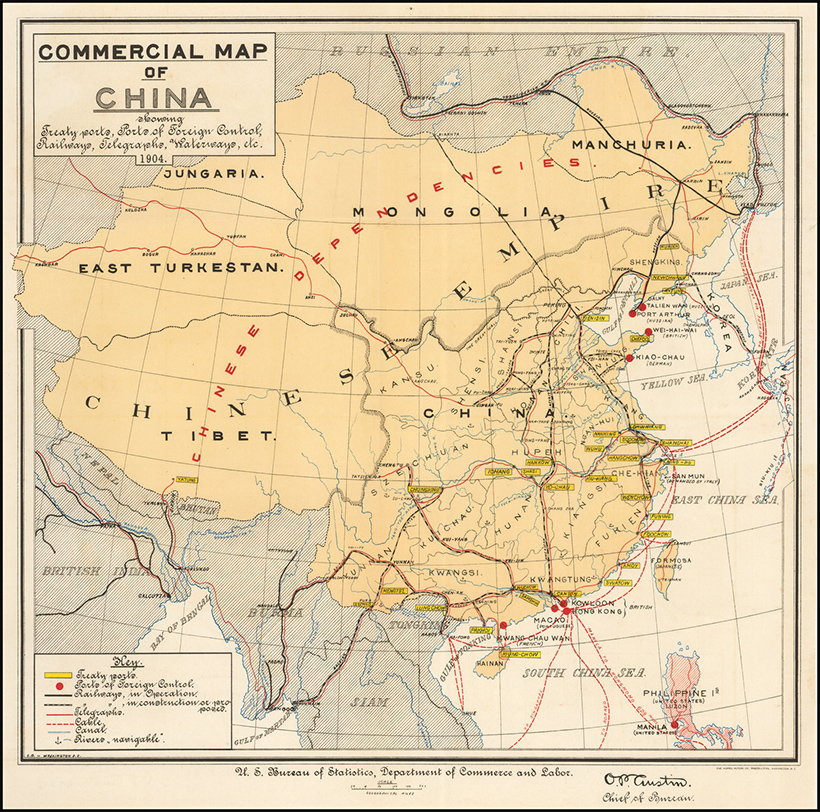

Early Sino-Western trade was restricted by the Qing emperors to three ports, and after 1757, just one, in what became known as the Canton System. This name came from the one remaining port city of the same name, present-day Guangzhou. Foreign trade was tightly monitored and subject to stiff tariffs, and Western traders chafed under these restrictions. So when in 1839, Chinese authorities moved to shut down opium smuggling—an important source of profit for foreign merchants—Western powers saw their chance and used the pretext to revise the terms of trade by force. In what became known as the Opium Wars, 1839-1842 and 1856-1860, first Great Britain and then an Anglo-French alliance defeated imperial China and imposed punitive treaties that included indemnities and lowered tariffs, but also expanded the number of ports open to foreign traders, first to five and by 1911, to more than 50.

Westerners were exempted from local laws, Christian missionaries were allowed to proselytize freely, and the opium trade was legalized. Hong Kong was also ceded to Great Britain at this time. The Treaty Port Era, also known as the Century of Humiliation, was perhaps too much for the country to bear. The weakened central government was beset by popular unrest, including the Taiping Rebellion (1850–64), which killed 20 million people, and the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), so-named for the secret society that led the movement, the Righteous and Harmonious Fists. Eventually, the last Chinese emperor was deposed and a republic declared in 1911. Nevertheless, the government was too weak to impose its will, and was repeatedly challenged by warlords. So as we approach the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, and the period covered by our visualization, we find China weakened internally by civil strife, and externally by Western powers.

The History of this Century-Old Pie Chart

Aspects of Principal Exports of Chinese Goods to Foreign Countries captures Chinese exports for 1914, and comes from The New Atlas and Commercial Gazetteer of China: A Work Devoted to Its Geography & Resources and Economic & Commercial Development. Originally published in 1917 and edited by Edwin J. Dingle for the Far Eastern Geographical Establishment, the volume contains a wealth of data for the period. According to the book’s Preface, it “seeks to give all the information that is essential to the business-man in regard to a country… about which less is known than in regard to any similar area in the world.” The visualization breaks down total Chinese exports for 1914 in haikwan taels (hk. tls.), a unit of silver currency used to collect tariffs. In 1907, one haikwan tael was worth $0.79 U.S. dollars. Official figures come from the Chinese Maritime Customs Service. This was set up by foreign consuls after the First Opium War to collect tariffs to guarantee the payment of treaty indemnities. Exports in 1914 represented 345 million hk. tls., a 14.4% decrease from 1913, likely owing to the outbreak of the First World War that same year. Apart from “Other Metals and Minerals, Sundries, etc,” which served as a catch-all category, the largest categories were silks and teas of various types, representing 22.6% and 10.4% of total exports respectively. Below are some more details that emerge from this visualization.

All the Tea in China

The Chinese tea trade was the subject of another visualization in the Atlas. It shows that China had been steadily losing ground to British India. Between 1888-1892 Chinese exports to Great Britain were 242 million pounds against India’s 105 million pounds. By 1912-1913, India had surpassed China to export 279 million pounds against 198 million pounds. In 1914, the majority of Chinese exports went to Russia, 902,716 piculs in all. A picul is equal to “as much as a man can carry on a shoulder-pole” or about 133 pounds.

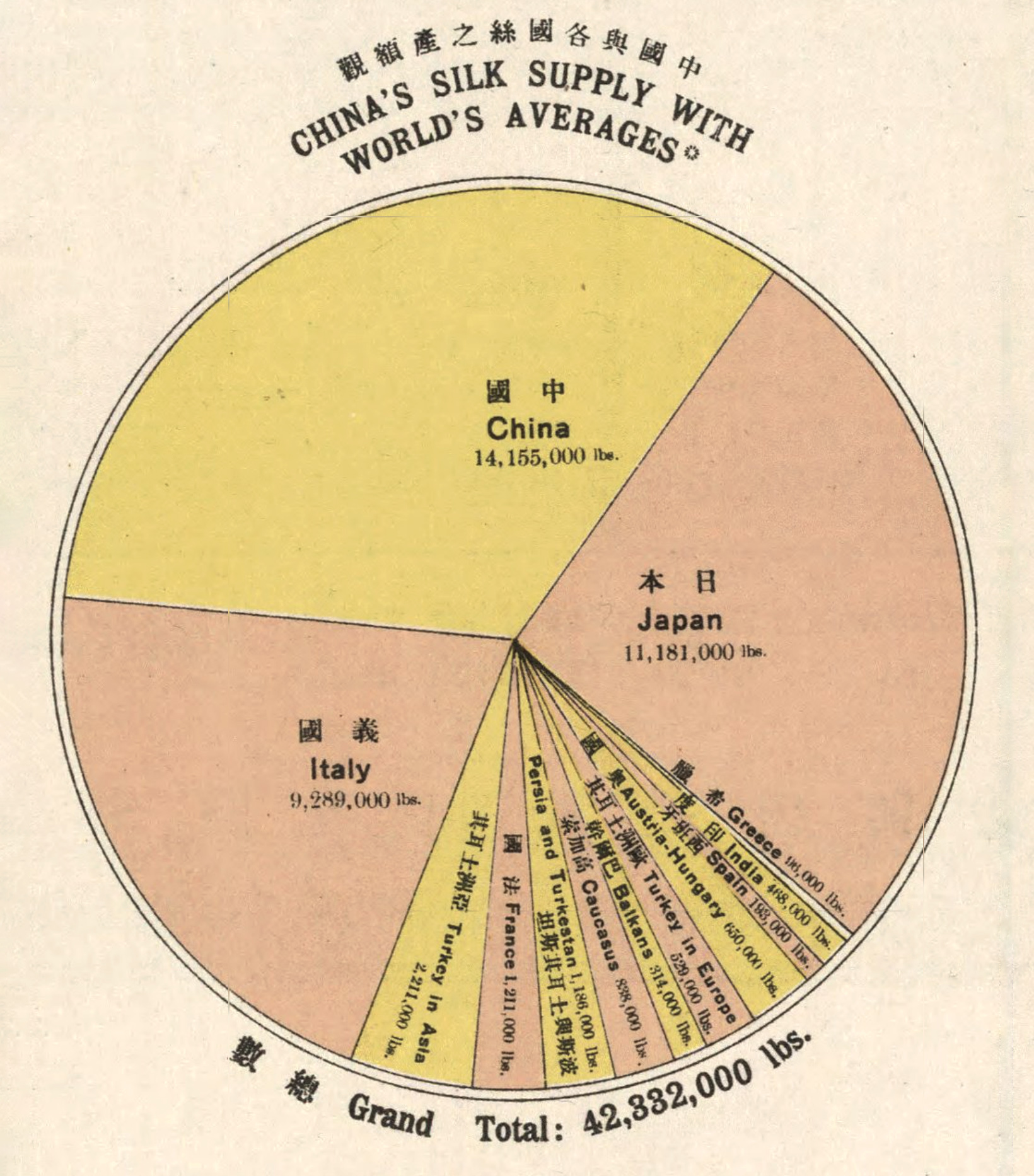

The Silk Road to Profits

Silk has long been in demand in the West as a luxury good, giving its name to the overland trade route that connected East and West for centuries: the Silk Road. In 1914, China was the largest producer and exporter of silks in the world. On an annual basis, China averaged 14 million pounds, compared to the number two spot, Japan, at 11 million pounds, and number three, Italy, at 9 million pounds. Together, these three controlled 81.7% of the global silk trade.

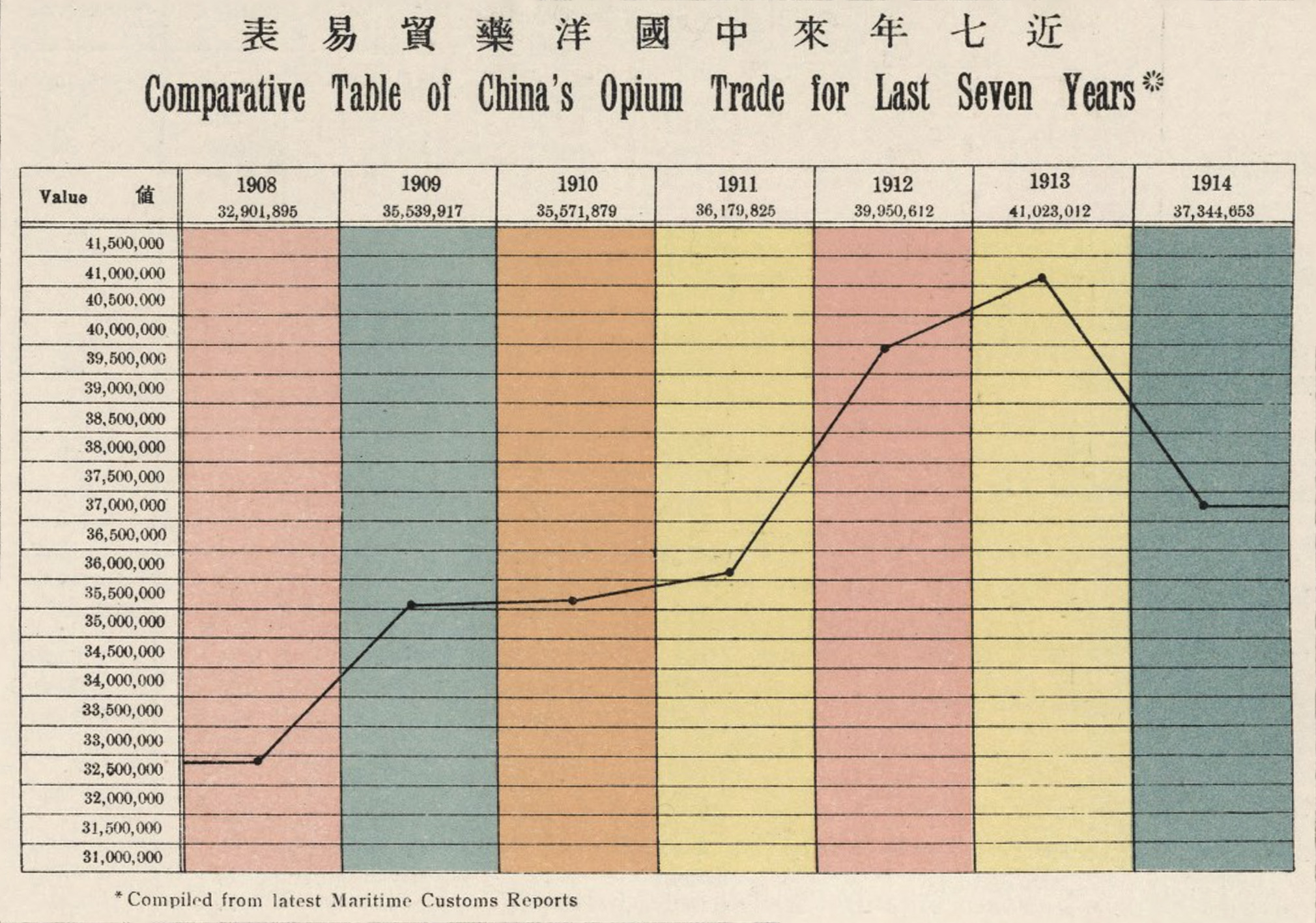

The Opium of the Masses?

The opium trade, the pretext that opened China to foreign trade, was still big money in 1914. A total of 37 million hk. tls. were imported in 1914 from India, up 11.9% from 1908. This is actually down from a peak of 41 million hk. tls. in 1913.

In 1907, China signed the Ten Year Agreement with India, which ultimately phased out the opium trade. By 1917 the trade was all but extinguished.

Back to the Future

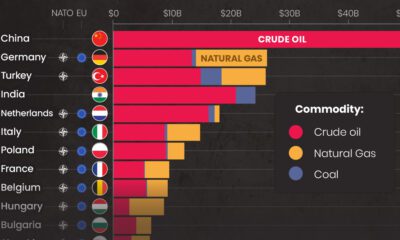

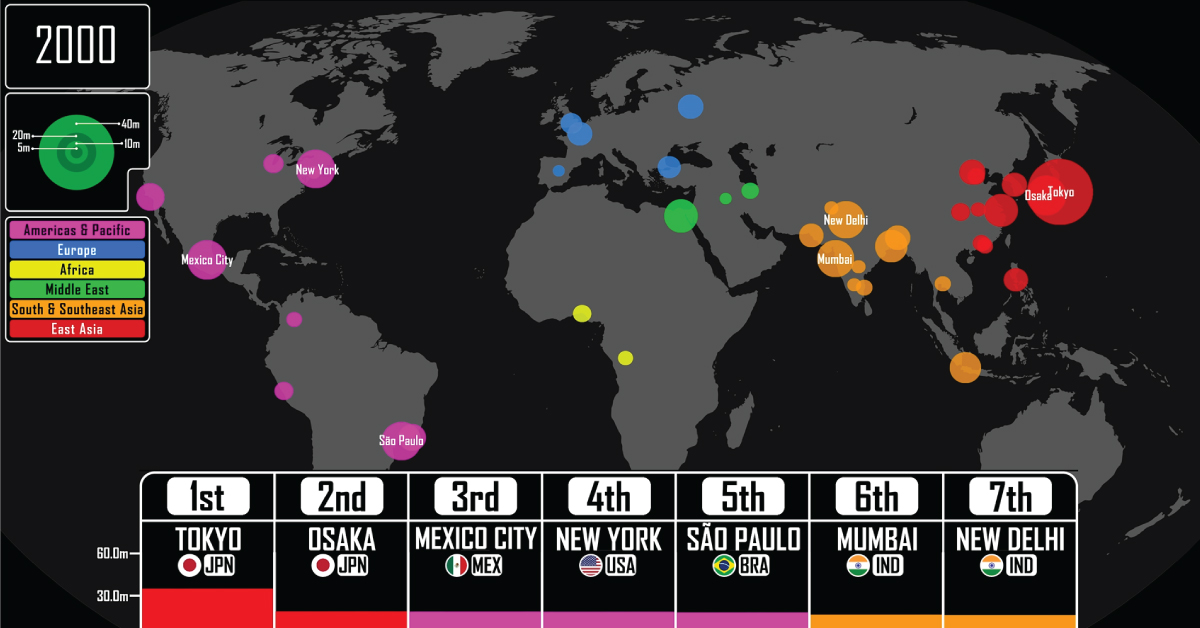

The Aspects of Principal Exports of Chinese Goods to Foreign Countries is a far cry from the contemporary trade picture. China’s top export in 2021 was in the category “telephones for cellular networks or other wireless networks,” and was worth $147.1 billion. But it’s worth noting that China today is a direct result of this period. The resentment created during the Century of Humiliation would eventually help lead to Mao Zedong, the Long March, and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. And in 1979, the Chinese central government would set up the first of their own “treaty ports,” in the form of special economic zones, places where foreign companies could set up shop. But this time, it wasn’t foreign powers who were making the rules. on Cities—settlements that are densely populated and self-administered—require many specific prerequisites to come into existence. The most crucial, especially for much of human history, is an abundance of food. Surplus food production leads to denser populations and allows for people to specialize in other skills that are not associated with basic human survival. But that also means that cities usually consume more primary goods than they produce. And their size requires a host of many other services—such as transport and sanitation—that are traditionally expensive to maintain. So maintaining large urban centers, and especially the world’s largest cities, was a monumental task. Mapper and history YouTuber Ollie Bye has visualized the seven largest cities in the world since 3,000 BCE. His video covers cities with a minimum population of 10,000 and hints at historical events which led to the establishment, growth, and eventual fall of cities.

The World’s Largest City Throughout History

With any historical data, accuracy is always a concern, and urban populations were rough and infrequent estimates up until the Industrial Revolution. Bye has used a variety of data sources—including the UN and many research papers—to create the dataset used in the video. In some places he also had to rely on his own estimates and criteria to keep the data reasonable and consistent:

In early history, some cities didn’t have given population estimates for long periods of time, and had to be equalized or estimated through other sources. For example, Babylon had a population estimate at 1,600 BCE (60,000) and at 1,200 BCE (75,000) but none in the 400 years between. Cities that only briefly climbed above a population of 10,000, or that would have made the largest cities ranking for only a couple of years (and based on uncertain estimates), were not included.

Here’s a look at the largest city starting from the year 3,000 BCE, with populations listed in millions during the last year of each city’s “reign.” Cities are also listed with the flags of current-day countries in the same location.

Ancient Cities in the Fertile Crescent

Considered the “cradle of civilization,” the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East was home to all seven of the largest cities in the world in 3,000 BCE. The Sumerian city of Uruk (modern-day Iraq), allegedly home to the legendary king Gilgamesh, topped the list with 40,000 people. It was followed by Memphis (Egypt) with 20,000 inhabitants. For the next 1,700 years, other Mesopotamian cities in modern-day Iraq and Syria held pole positions, growing steadily and shuffling between themselves as the largest. 2,250 BCE marked the first time a different Asian city—Mohenjo-Daro (modern-day Pakistan) from the Indus Valley Civilization—found a spot at #4 with 40,000 people. The table below is a quick snapshot of the seven largest cities in the world for from 3,000 BCE to 200 CE. Again, populations are listed in millions. It wasn’t until 1,250 BCE that the top two spots were taken by cities in different regions: Pi-Ramesses (Egypt) and Yin (China), both with more than 100,000 residents. Egyptian cities would continue to be the most populous for the next millennium—briefly interrupted by Carthage and Babylon—until the start of the Common Era. By 30 CE, Alexandria was the largest city in the world, but the top 10 had representatives from the Middle East, Northern Africa, and Asia.

All Roads Lead to Rome

One city in Europe meanwhile, was also beginning to see steady growth—Rome. It took until halfway through the 3rd century C.E. for Rome to become the most populous city, followed closely still by Alexandria (Egypt). Meanwhile in Iraq, Ctesiphon, the capital of the Sasanian empire was growing rapidly. Towards the end of the 3rd century, the Roman empire was divided into two, with Constantinople becoming the new capital for the Eastern half. Consequently, it had outgrown Rome by 353 and become the world’s most populous city, and for the next few centuries would reclaim this title time and time again.

The Largest Cities Reach 1 Million

In the 9th century, Baghdad became the first city to have 1 million residents (though historians also estimate Rome and the Chinese city of Chang’an may have achieved that figure earlier). It would be nearly nine centuries until a city had one million inhabitants again, and Baghdad’s reign didn’t last long. By the 10th century, Bian, the capital of the Northern Song dynasty in China, had become the largest city in the world, with Baghdad suffering from relocations and shifting political power to other cities in the region. From the 12th century onwards, Mongol invasions in the Middle East and Central Asia severely limited population growth in the region. European cities too were ravaged in the 14th century, but by plagues instead of marauders. For the next few hundred years, Cairo (Egypt), Hangzhou (China), and Vijayanagara (India) would top the list until Beijing took (and mostly held onto) the top spot through the 19th century.

Industrial Revolution and Rapid Urbanization

The start of the Industrial Revolution in the UK—spreading to the rest of Europe and later on the U.S.—led to hitherto unseen levels of urban population growth. Factories needed labor, which caused mass emigration from the rural countryside to urban centers of growth. In 1827, London passed Beijing to become the largest city in the world with 1.3 million residents. Over the next 100 years, its population increased nearly 7 times, remaining the most populous city until the end of World War I, by which time it was overtaken by New York. From 1920 to 2022, the world population quadrupled thanks to improvements in farming and healthcare, and cities saw rapid growth as well. The beginning of the 20st century saw the top 10 largest cities in the world in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. By the 21st century however, growth shifted away to other parts of the world and by 2021, the top seven had cities only from Asia and the Americas. Tokyo, which took the top spot in 1954, is the largest city in the world today with a population of 37 million (including the entire metropolitan area). It is followed by New Delhi with 31 million, but by 2028, the UN estimates that positions will switch on the leaderboard and New Delhi will overtake Tokyo.

What Does Population Growth Say About the Past (and Future)?

The rise and fall of cities through the sands of time can give us insight into the trajectory of civilization growth. As civilizations grow, become richer, and reach their zenith, so too do their cities blossom in tandem. For example, of the modern-day seven largest cities in the world, four of them belong to countries with the 10 largest economies in the world. Meanwhile, sudden falls in urban population point to turbulence—political instability, wars, natural disasters, or disease. Most recently Ukraine’s cities are seeing depopulation as residents flee conflict zones, raising the specter of a demographic crisis for the country should the war continue. Thus, tracking the size of urban population can help policymakers forecast future roadblocks to growth, especially when prioritizing sustainable growth for a country.